President Erdogan will be paying a formal visit to Egypt on February 14th. Perhaps he wants to endear himself to President Sisi to whom he had referred with unkind words in the past on Valentine’s day. It is early to judge how the visit will affect the relations between the two countries. Nevertheless, they will likely improve not only because there is a shift of mood on both sides favoring improvement, but also because it would be difficult to envision their growing worse since they appeared to have hit a rock bottom not too long ago.

Egypt and Türkiye, as two leading countries in the Middle East, have had uneven relations throughout history, but always marked by courtesy. Egypt was one of the first regional countries to break away from the Ottomans, but relations between the two countries remained close not only because the ruling house was of Turco-Ottoman origin but also because Egypt discovered that it was important to have the Ottoman Empire on its side as it tried to defend itself, not particularly successfully, against British efforts to become the prevailing force.

After the founding of the Turkish Republic, the relations between the two countries were cordial but entered a difficult period after the Egyptian revolution. The land reform implemented by the Colonels’ Revolution ended the domination of Egyptian peasants by landlords mostly of Turkish origin. More importantly, while Türkiye was concerned about the Southward expansion of the USSR and sought closer integration with the Western security community, the Egyptian government was trying to expand its independence by driving away Western powers, most notably Britain, from dominating it. It worked closely with the Soviets as a means of reducing Western influence. Gradually, Egypt moved closer to the US but this did not much affect Turkish-Egyptian relations.

The end of the Cold War and the Soviet Union on the one hand, and the change in the Turkish economy from import substitution to export led growth on the other, led to a new opening in relations. Turkish businesses felt particularly attracted to Egypt. It seemed to be a country where they could move their factories as labor costs in Turkey were beginning to mount. It was centrally located for reaching African markets. With a huge population, the country also constituted a big market in itself. The Egyptian president at the time, Husnu Mubarak, worked hard to bring them together after Türkiye threatened to send its army to Syria if it continued to offer a home to the Kurdish terrorist organization, the PKK. Before the Arab Spring came, the two countries were humming along and looking forward to developing closer relations.

The Arab Spring showed that most of the regimes in the Middle East were unpopular with the masses. Compared to them, Türkiye seemed to be a bastion of stability and prosperity. Türkiye decided that the new conditions allowed it to become the leader of a Sunni-dominated region. In reaching this policy shift, the Turkish leadership judged that the Muslim Brotherhood, as the best-organized opposition in the region, would carry the day in elections. Although the Brotherhood might have been better organized than others, however, they did not attract the unqualified support of large electoral majorities. It was not clear that the Brotherhood had prepared itself for democratic governance, either. In the end, it was able to win a modest majority in Egypt and form the government. Its attempt to Islamicize Egyptian society backfired, however. The brief Islamic experiment tinted with authoritarian rule was ended by a broadly supported military intervention led by General al-Sisi.

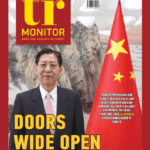

The Sisi government received support from the traditional regimes in the region as well as from the major international actors including the US, the EU, Russia and China. In contrast, the Turkish leadership whose dreams of becoming a regional leader were shattered, became an arch-enemy of Egypt. Pronouncing insults regarding al-Sisi became commonplace. But more importantly, Türkiye and Egypt became rivals in international politics. Al-Sisi worked with Greece, Greek Cyprus and Israel on defining exclusive economic zones in the Eastern Mediterranean and making plans to send the recently discovered natural gas in the seabed to European markets by avoiding using pipelines through the Turkish landmass. In Libya, Türkiye and Egypt backed different sides. Egypt befriended Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states of whom Türkiye was highly critical.

Isolated in its neighborhood, pushed into dire economic straits by pursuing highly unorthodox economic policies, seeing that the regional policy it chose to pursue has totally failed, Türkiye has now decided to make a comeback and reconstruct its relations in the region. Seeing Turkey get back into the fold may be welcome, but since this is a Turkish desire, Egypt just like the Gulf States before it, is unlikely to welcome Turkey with open arms. It will take time for wounds to heal. After a prolonged negative history, Erdogan’s trip to Egypt hopefully marks a good beginning.